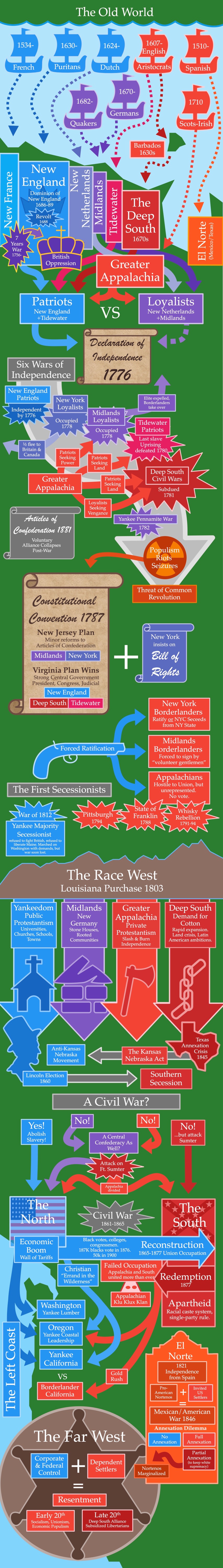

The timeline above is an attempt to illustrate Colin Woodard’s book American Nations. Woodard argues that our current political differences are not the result of a simple urban/rural divide. Rather they can be traced back to deep cultural divisions present in the original 13 colonies.

Woodard builds his thesis on the observation that immigrants and their children tend adopt the culture of the places they immigrate to, rather than retaining the culture of the places originate from. The first groups to settle North America laid down a “cultural DNA” which came to define not just the identity of their own descendants, but also the identities of later waves of immigrants who assimilated into these groups. For example, the current residents of New England may not be the direct descendants of the original Puritans that colonized New England, but they are nevertheless shaped by the original Puritan culture. (The tragic exception to this principle is the Native American culture that preceded European colonization. When colonists first came to America, they did not assimilate with the existing inhabitants. Rather the natives were driven to near extinction by disease and expulsion.)

According to Woodard, there are eleven rival “nations” in North America. Six of these nations are central to the early history of the United States. New England was colonized by Puritans seeking to build the kingdom of God in the New World. Tidewater (Virginia) was colonized by English aristocrats living on country estates manned by slaves. New Amsterdam (NYC) was colonized by Dutch merchants, The Midlands (Pennsylvania) was colonized by Quaker pacifists, and The Deep South was colonized by the sons of Barbados slaveholders. And finally, there was Greater Appalachia, colonized by poor, illiterate “borderlanders” of Scots-Irish and Northern English descent who poured into the back country in many of the colonies and much of Appalachia.

For most of the colonial period, these new nations were relatively neglected by their mother empires. This allowed them to put down cultural roots and form their own governments. When Great Britain decided to tax the colonists after Seven Years War (1756-1763), New England revolted. Representatives from each of the colonies met in 1776 to assess the situation, ultimately deciding to declare independence from Britain. However, strong majorities in New Amsterdam and the Midlands opposed independence. There was also profound ambivalence in Appalachia and the Deep South.

The Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War was not really one single war. Rather, it consisted of six or more separate wars, each fought for separate reasons, and each with separate sets of belligerents:

- New England was the most anti-British of the American Nations and it gained de-facto independence in 1776, less than a year after fighting began.

- New Amsterdam was a pro-loyalist stronghold which held out till 1778 when it was conquered and occupied by patriots from the other nations. Over half the population fled to Canada and Britain.

- The Midlands was also pro-loyalist and was conquered by patriot forces in 1778. The Philadelphia-based Quaker leadership was exiled and borderlanders from inland areas took over.

- Tidewater saw sporadic slave revolts incited by loyalists which were finally put down in 1780.

- The Deep South suffered a series of civil wars that lasted until 1781. The fiercest fighting was not between Brits and patriots, but between loyalist Appalachians and patriot slaveholders. The loyalist Appalachians had no great love for the British. They were simply fighting against the violent and authoritarian rule of the slaveholding class.

- The Yankee Pennamite War was a longstanding conflict between Yankees and Midlanders which was finally resolved in 1782 in favor of the Midlanders.

The Revolutionary War was as much a war between Americans as it was a war with the British. This set a bad precedent for future cooperation between the colonies. After the British retreated, populist violence continued to plague the colonies and the leadership worried that their territories were descending into “common revolution.”

The US Constitution

The 1787 Constitutional Convention attempted to address the growing crisis. Two plans were put forward. The New Jersey Plan consisted of minor reforms to the previous Articles of Confederation, a weak alliance similar to today’s European Union. This plan was supported by the Midlands and New Amsterdam. The Virginia Plan called for a strong central government divided into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. This was supported by Tidewater, New England, and the Deep South. New Amsterdam was persuaded to support the Virginia Plan after a Bill of Rights was added, which was modeled on the Dutch 1664 “Articles of Capitulation.”

Ultimately, the US Constitution was ratified unconstitutionally. The borderlanders of Greater Appalachia were absolutely opposed to any form of centralized government (many are still opposed today). New York borderlanders were forced to sign after New Amsterdam threatened to secede from the state. Representatives for the Midland borderlanders were dragged from their homes and forced to sign by “volunteer gentlemen.” And Appalachia was almost entirely unrepresented, so none of them even had the chance to vote.

Early Attempted Secessions

This underhanded ratification process led to a series of attempted secessions from the new union: The State of Franklin (1788), the Whiskey Rebellion (1791-1794), and the March on Pitsburgh (1794). New England even attempted secession during the War of 1812. During the war, the Yankees were passionately pro-British while the rest of the US was officially on the French side. The majority of New Englanders favored secession from the United States and a new alliance with the British. They marched on Washington DC with an ultimatum. However the British signed a peace treaty with the US, making the Yankee effort dead on arrival.

The Race West

Tensions in the young country were eased by the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Now, restless citizens could pursue independence in the endless western expanse. New Englanders, Midlanders, Appalachians, and Deep Southerners all raced west. Along the way, each group spread their own distinct set of cultural values. The Yankee pioneers were “public protestants” who built institutions: schools, churches, and town halls. Their legacy can be seen in the many universities they established across the country. Midlanders of German and Scandinavian descent established rooted communities which still retain their distinct ethnic cultures. The Appalachians slashed and burned their way across the continent, seeking independence and adventure. They were “private protestants” with a focus on personal salvation rather than religious conformity. Their legacy can be seen in America’s “Bible belt.” The Deep South set the stage for the Civil War by aggressively adding new slave states to the union. The annexation of Texas as a slave state caused panic in the North and added fuel to the growing abolitionist movement. When Abraham Lincoln (a northerner with abolitionist tendencies) was elected president, the South immediately seceded from the Union.

The Civil War

After southern secession, New Englanders were the only ones gunning for war. The Midlands and Appalachia hoped to form their own “middle” confederacy and the Deep South hoped for a peaceful divorce from the North. However, the South’s foolish attack on Ft. Sumter forced everyone to take sides. Ultimately, the Midlands joined the North, and the Appalachians divided themselves between Confederates and Unionists.

Reconstruction

After the Union victory, Yankees occupied the South, enforcing black suffrage, education, and integration. This caused deep resentment, particularly in Appalachia, where newly freed blacks competed with the white population for jobs and land. Reconstruction ended in failure when the Yankees pulled out in 1877. The South instituted a racial caste system, maintained effective control over the formerly enslaved population. 187,000 blacks had voted in the presidential election of 1876 due to the protections of Reconstruction. But by 1900, that number had dwindled to 50,000. The Klu Klux Klan emerged in Appalachia in 1865, a place were resentment and racism ran deepest.

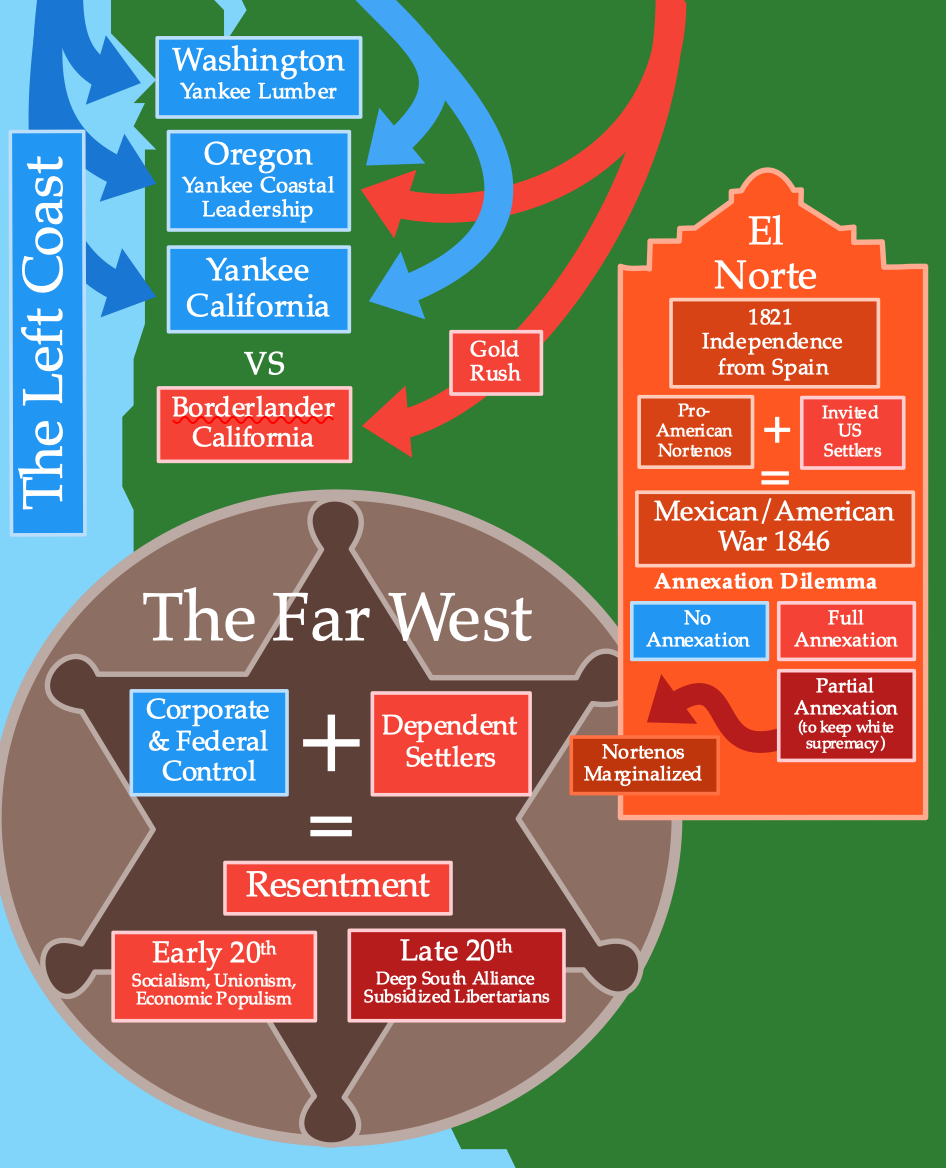

The Left Coast and Far West

In the meantime, Yankee-owned businesses began capitalizing on lumber and mineral interests near the west coast. Borderlander immigrants trudged along the California trail hoping to strike gold. This alarmed Yankees, who worried that the Far West was descending into godless anarchy. Pioneers of New England descent joined the trek west as part of a divine “errand in the wilderness,” which was meant to civilize, proselytize, and extend the Christian nation.

The Far West was full of natural resources waiting to be extracted. But much of it was also uninhabitable desert. This meant that the settlers had to be heavily subsidized by federal and corporate entities: massive irrigation projects, railroads, supply chains, etc. The myth of the independent homesteader broke down, but it never completely died. This led to a culture of “subsidized libertarianism,” an independent-minded populace, resentful of federal and corporate control, but still entirely dependent upon it.

El Norte

Much of the Far West was originally part of Mexico. The northern Mexicans inhabiting the Far West (nortenõs) resented the corrupt rule of the Mexico City elite. They were inspired by the American Revolution and hoped one day to have an independent state of their own. The nortenõs invited American settlers into their territory, intent on sparking a new war of independence. They got the war they wanted in 1846, but sadly, the American conquerers were even more oppressive than the Mexico City elite had been. Many of the nortenõs were driven from their homes into today’s Mexico proper. Today, the Mexican immigrants coming across the southern border include the descendants of the original nortenõs. They are returning to their lands of origin.

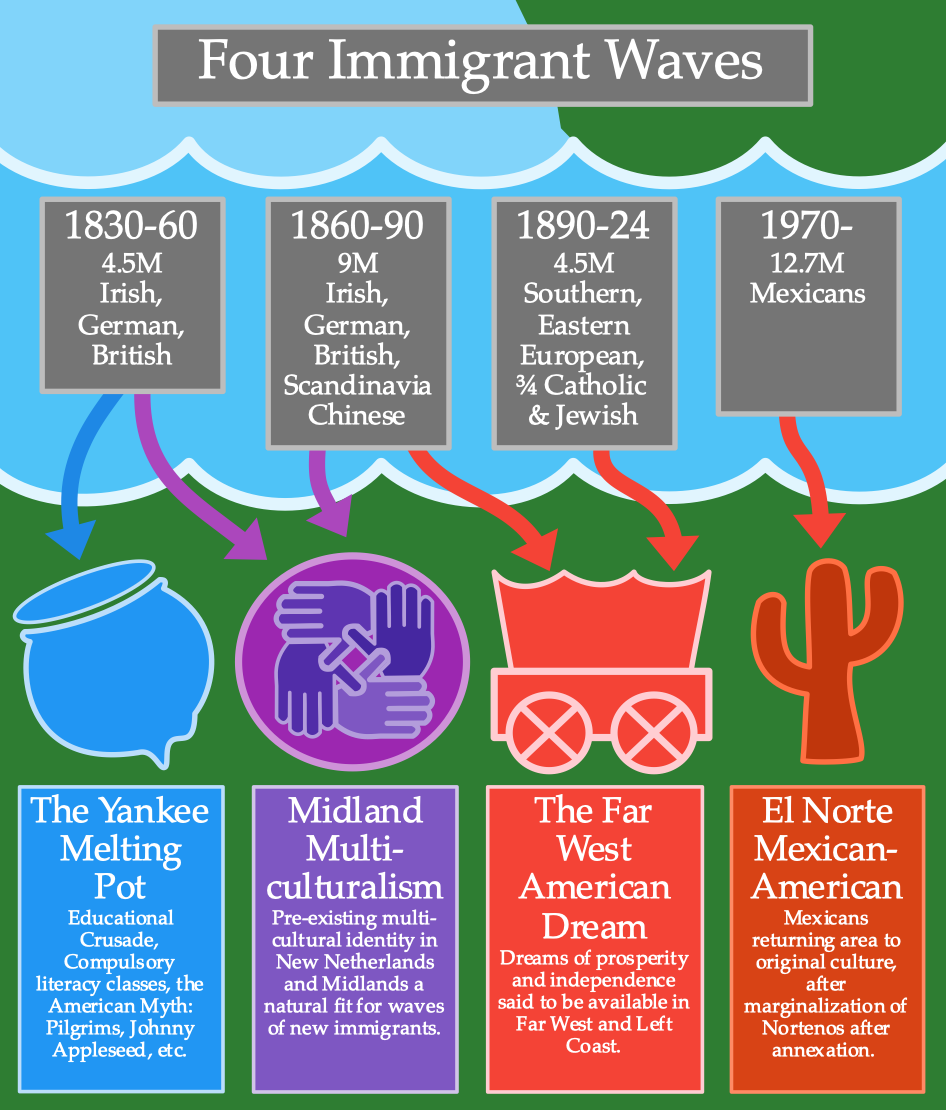

Immigrant Waves

Woodard divides his study of US immigration into four distinct “waves.” The chart above illustrates Woodard’s argument that each immigrant wave is related to a particular form of American identity. These identities emerged from the geographical locations of “nations” that each wave of immigrants settled in.

1. The Yankee Melting Pot: Immigrants who settled in Yankee areas were subjected to the Yankee’s patriotic and religious education, compulsory literacy, and communitarian values.

2. Midland Multiculturalism: Immigrants who settled in the Midland areas were encouraged to respect diversity. This reflected the tolerant ethos of the existing Midland communities.

3. The Far West American Dream: Immigrants who migrated to the Far West adopted the values of independence and freedom embodied by the original borderlander pioneers.

4. El Norte Mexican-American: The original nortenõs of northern Mexico were independent-minded colonizers who resented the corrupt rule of Mexico City. The return of the nortenõs in our day represents the marriage of two similar cultures: Northern Mexican and Far West American. In spite of nativist fear-mongering, nortenõs tend to share the conservatism of their gringo neighbors in the Far West. However, racist attitudes have been known to push them into political alliances with liberal Yankees.

20th Century Political Coalitions

During the 20th century and into the 21st, there have been three major political coalitions that have emerged from the early American nations:

- The Northern Coalition includes New England, New Amsterdam, and the Left Coast. Its political character is still influenced by the “public protestantism” of the original Puritans. The descendants of the Puritans may have abandoned the religious zeal of their ancestors, but not their zeal for social change. Puritans evolved to become Unitarians advocating a social gospel of abolition, prohibition, and suffrage. Unitarians evolved to become liberal humanists advocating “secular puritanism” which aggressively promotes science, social justice, and environmentalism. New Amsterdam’s contribution to the Northern Coalition included the Greenwich Village counter-culture of radical politics and artistic innovation. Greenwich Village’s marriage to secular puritanism gave rise to Northern Youth Movement (hippies).

- The Swing Nations include the Midlands, El Norte, and the Far West. Labor activism was a big part of early Far West politics but shifted to libertarianism in the later half of the 20th century. Today, the Far West usually aligns itself with the Dixie Coalition. In the later half of the 20th century, El Norte joined the Northern Coalition, thanks to the work of activists like Caesar Chavez. Through it all, the Midlands have been the only area to hang on to their swing state status, although this could be change if El Norte swings back to the Right.

- The Dixie Coalition includes Greater Appalachia, Tidewater, and the Deep South. Its identity is defined by its opposition to the Northern Coalition’s progressive zeal. The secular puritanism of New England led to a fundamentalist backlash emphasizing biblical literalism and opposition to evolution. When the Northern Youth Movement spun out of control during the 60s and 70s, Evangelical Christianity emerged as a countervailing political force.

The Great Party Switch

During the Civil Rights movement, the Northern Coalition and the Dixie Coalition switched political parties. Democrats became Republicans and Republicans became Democrats. Opposition to civil rights wasn’t the only reason for this switch. Yankees had been defecting to the Democratic party throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. African Americans had been loyal Republicans throughout the 19th century but began switching to the Democratic party during FDR’s administration. Given the growing popularity of the Democratic party among northerners and blacks, southern whites began to feel like strangers in their own party. The Civil Rights Movement was the straw that broke the camel’s back. When Southern Democrat Lyndon Johnson decided to throw their support behind the Civil Rights movement, it was seen as a betrayal by his southern constituencies.

Late 20th and Early 21st Century Political Warfare

Since this political realignment, three forms of conflict have dominated American politics: corporate wars, culture wars, and foreign wars.

- Corporate wars: Dixie bloc policies ensured that the Deep South and the Far West became low-wage resource colonies for their wealthy elite. Low taxes and wages have lured away most Yankee and Midland Manufacturing. However, knowledge clusters in Silicon Valley and along Boston’s Route 128 have created new centers of tech power in New England and the Left Coast.

- Culture wars: Since the 60s, the culture wars have been defined by northern coalition majorities supporting social change and Dixie coalition majorities defending traditional order.

- Foreign wars: In general, the Northern coalition is anti-interventionist and anti-imperialist, although the recent wars in the Middle Eastern wars have shown that the northern coalition is willing to engage in foreign wars when they are pursued for idealistic or intellectual reasons. The Dixie coalition is usually more hawkish and prefer a unilateral and honor-bound approach to foreign engagement. They can become anti-interventionist if they perceive military engagement as being part of an international or multilateral project.

Conclusion

When I first encountered American Nations I found the thesis to be a bit far-fetched. I had always understood the Right/Left division in the United States to be a result of a simple urban/rural divide. However, a closer look at Woodard’s data convinced me that he is on to something. Electoral maps separated by county rather than state show consistent political orientations throughout US history. And when the African American vote is controlled for, the urban/rural divide in red states all but disappears. Jayman’s Blog has collected lots of additional data supporting Woodard’s thesis. For anyone who is still skeptical, I strongly suggest reading this supporting material and taking a closer look at the electoral maps. Thanks for reading!

Leave a comment